- Home

- Visit

- Education

- Field Trips

- Summer Camps

Winter Masquerade 2025

Thank you to all who attended this year's Winter Masquerade! Guests enjoyed a lovely evening of colonial music, dancing, and a delicious dinner at Radnor Hunt's historic facility in Malvern.

When

Saturday,

February 22, 2025

5 PM to 9 PM

Where

Radnor Hunt Club

826 Providence Rd.

Malvern, PA 19355

Attire

Semi-Formal, Colonial Clothing,

or Masquerade Costume.

The choice is yours!

Colonial Farmstead is pleased to feature

West Point Thoroughbreds Racehorse Ownership Experience

3% interest in 2-year-old colt named Essential Charm during his racing career

The winning ticket holder will experience first-hand what it’s like to be a Thoroughbred racehorse owner in the Sport of Kings! You can cheer on your horse at the races, enjoying all the thrills without the maintenance bills. You’ll become affiliated with America’s leading racing partnership, West Point Thoroughbreds, which selected and campaigned 2022 Horse of the Year, World’s Best Racehorse, & Breeders’ Cup Classic Champion Flightline.

Congratulations to the winner!

Essential Charm is an unraced 2-year-old colt trained by Arnaud Delacour, with his primary operations based at Maryland’s Fair Hill Training Center - a central hub to racetracks in Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia. Essential Charm is currently in Ocala, FL learning his lessons. You’re able to experience all the anticipation of bringing an unraced horse to the track while being updated on the horse’s progress from youngster to professional racehorse. The colt is expected to compete on the Mid Atlantic and Florida racing circuits late summer of 2025. Essential Charm’s pedigree is loaded with stakes winners. His father, Essential Quality, won the Belmont and Travers Stakes and was named champion twice during his racing career. His mother, Adorable Miss, has produced two exciting graded stakes winners campaigned by West Point, Battle of Normandy and Cugino.

This incredibly awesome ownership experience includes:

- Access to online communications about your horse and the entire West Point stable

- Access to paddock and (hopefully) winner's circle

- Invitations to Partner and industry special events

- You get all the fun and we guarantee NONE of the training bills. You’ll receive any net racetrack purse distributions the horse may earn during his racing career.

West Point Thoroughbreds is the leading racehorse partnership company in America, managing over 130 horses and more than 650 Partners. Since 1991, West Point runners have won 1,170 races and over $86 million in purses. West Point selected 2022 Horse of the Year & Breeders’ Cup Classic unbeaten champion Flightline out of the 2019 Saratoga yearling sale, and was a minority owner of 2017 Kentucky Derby winner Always Dreaming. Fair market value: $5,880

Learn more about West Point Thoroughbreds.

Read More

Thank you to our Sponsors!

Diamond Sponsors

Ruby Sponsors

Lisa Bell

David Moser

Gold Sponsors

Susan Hodge

Laura Stokely

Sapphire Sponsors

Maria Diesel

Advertisers

- Wilson Oil and Propane

- PentaHealth

- White Horse Village

- Den of Antiquity

- Sandy Kauffman and Company

Auction Donors

- West Point Thoroughbreds

- Keystone Woodturners

- Three Potato Four

- Mary-Chilton Van Hees

- Susan Hodge

- Lisa Bell

- Pilates and More

- Turning Point Restaurant

- Mom's Organic Market

- Philadelphia Orchestra

- Philadelphia Ballet

- Opera Philadelphia

- Oliver Pluff & Co.

- Regal Cinemas

- Sarah Farnsworth

- Cindy Faulkner

- Chuck Barr

- Maury Hutelmyer

- Chris Reardon

- Bruce Snyder

- Leslie Roes

- Museum of the American Revolution

- Bob Deane of the Potter's Guild of Wallingford

- La Locanda Italian Restaurant

- Black Powder Tavern

- Chadds Ford Tavern

- Serendipity Stables LLC

Proceeds from the Winter Masquerade are used to support our historic farm operations, care of our heritage breed animals, and our many education programs, including field trips, outreaches, summer camp, and skills workshops.

Is your business or organization looking to support CPF? Become an event sponsor!

Not a Member? Join Today!

What is a Masquerade?

The desire to temporarily shed one’s identity and have a thumping good time seems to be universal across human cultures. In the eighteenth century, celebrations known as Masquerades became popular in Europe. Masquerades – which were also known as masked balls or mock-carnivals – had their origins in the unique celebration of Carnival, the period of time before the Christian season of Lent, in Venice beginning in the fifteenth century. In Venice particularly, Carnival-goers began to don elaborate masks as part of their celebrations. At their height, around 800 people attended masquerades every week and paying members of the public could attend masquerades at venues like the Haymarket Theater, Vauxhall Gardens, Ranelagh Gardens, or the Pantheon. By the eighteenth century, masquerades became a popular form of entertainment for many in England, who never wanted to miss an opportunity to mock continental Europeans.

A Flair for the Dramatic

At masquerades, attendees donned masks to disguise their identity, and often dressed in elaborate costumes. At private events, attendees might be tasked with discovering the identity of their fellow party-goers, but at larger events, attendees simply reveled in the chance to shed their identity, and assume that of another. The rich might dress up (or down) as chimney sweeps or sailors, while middle class bankers and merchants could show up as nobles or clergy. Just like the halloween costumes that we wear today, people attending eighteenth century masquerades tried to think of humorous outfits to wear that poked fun at aspects of British society. They might also write witty songs or poems to accompany their outfits that they would perform in front of the crowd.

Stick in the Colonial Mud

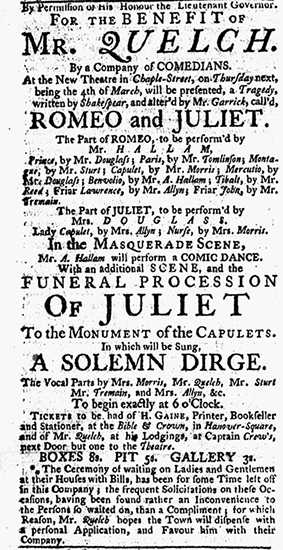

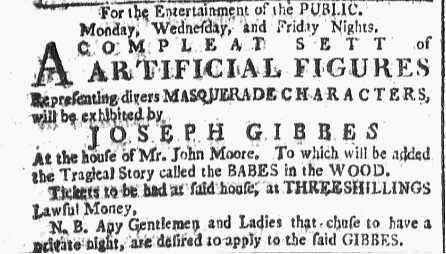

Just like today, there were people back then who didn’t like fun and opposed masquerades. They believed that the mixing of social classes was symbolic of societal decay. Indeed, some colonists – especially in New England – made a point of celebrating that Colonial Americans did not hold masquerades. What fun they must have been at parties. While Colonial Americans did not throw elaborate parties like their friends and foes across the pond, they were deeply interested in British masquerades. Well-to-do colonials had their portraits painted in masquerade costumes. In Philadelphia, a production of Romeo and Juliet featured a masquerade dance. Visitors to colonial cities could purchase porcelain figures in masquerade attire to decorate their dining tables or parlors.

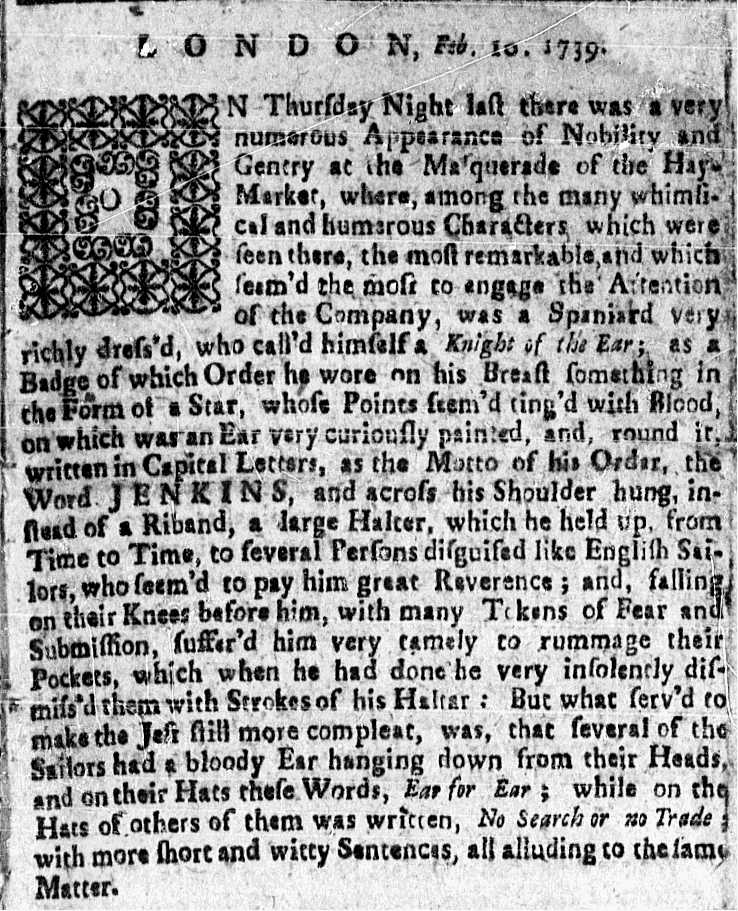

Newsworthy

Americans could read accounts of masquerades published in newspapers and read about the different costumes of the famous attendees. In 1763, the Boston News-Letter reported that “a lady of quality was dressed at the Duke of Richmond’s ma’querade, in such a manner, that which ever way she turned or moved, she represented a house at the corner of a street.”1 The exact meaning of this is open to interpretation. Later, in 1769, the Philadelphia Gazette informed readers of the costume of one Mrs. Ross “in the character of Night, displayed much fancy in the choice of her dress; it was a thin black silk, studded with stars, and fastened to the head by a moon, very happily executed.”2 By reading these, colonists in America could feel that they were part of the larger British Atlantic world.3

1Boston News-Letter, September 1, 1763.

2Pennsylvania Gazette, February 16, 1769.

3Jennifer Van Horn, “The Mask of Civility: Portraits of Colonial Women and the Transatlantic Masquerade,” American Art, vol. 23.